Sign the Statement: Truth Seeking, Democracy, and Freedom of Thought and Expression – A Statement by Robert P. George and Cornel West

The pursuit of knowledge and the maintenance of a free and democratic society require the cultivation and practice of the virtues of intellectual humility, openness of mind, and, above all, love of truth. These virtues will manifest themselves and be strengthened by one’s willingness to listen attentively and respectfully to intelligent people who challenge one’s beliefs and who represent causes one disagrees with and points of view one does not share.

That’s why all of us should seek respectfully to engage with people who challenge our views. And we should oppose efforts to silence those with whom we disagree—especially on college and university campuses. As John Stuart Mill taught, a recognition of the possibility that we may be in error is a good reason to listen to and honestly consider—and not merely to tolerate grudgingly—points of view that we do not share, and even perspectives that we find shocking or scandalous. What’s more, as Mill noted, even if one happens to be right about this or that disputed matter, seriously and respectfully engaging people who disagree will deepen one’s understanding of the truth and sharpen one’s ability to defend it.

None of us is infallible. Whether you are a person of the left, the right, or the center, there are reasonable people of goodwill who do not share your fundamental convictions. This does not mean that all opinions are equally valid or that all speakers are equally worth listening to. It certainly does not mean that there is no truth to be discovered. Nor does it mean that you are necessarily wrong. But they are not necessarily wrong either. So someone who has not fallen into the idolatry of worshiping his or her own opinions and loving them above truth itself will want to listen to people who see things differently in order to learn what considerations—evidence, reasons, arguments—led them to a place different from where one happens, at least for now, to find oneself.

All of us should be willing—even eager—to engage with anyone who is prepared to do business in the currency of truth-seeking discourse by offering reasons, marshaling evidence, and making arguments. The more important the subject under discussion, the more willing we should be to listen and engage—especially if the person with whom we are in conversation will challenge our deeply held—even our most cherished and identity-forming—beliefs.

It is all-too-common these days for people to try to immunize from criticism opinions that happen to be dominant in their particular communities. Sometimes this is done by questioning the motives and thus stigmatizing those who dissent from prevailing opinions; or by disrupting their presentations; or by demanding that they be excluded from campus or, if they have already been invited, disinvited. Sometimes students and faculty members turn their backs on speakers whose opinions they don’t like or simply walk out and refuse to listen to those whose convictions offend their values. Of course, the right to peacefully protest, including on campuses, is sacrosanct. But before exercising that right, each of us should ask: Might it not be better to listen respectfully and try to learn from a speaker with whom I disagree? Might it better serve the cause of truth-seeking to engage the speaker in frank civil discussion?

Our willingness to listen to and respectfully engage those with whom we disagree (especially about matters of profound importance) contributes vitally to the maintenance of a milieu in which people feel free to speak their minds, consider unpopular positions, and explore lines of argument that may undercut established ways of thinking. Such an ethos protects us against dogmatism and groupthink, both of which are toxic to the health of academic communities and to the functioning of democracies.

Robert P. George is McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence and Director of the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions at Princeton University.

Cornel West is Professor of the Practice of Public Philosophy in the Divinity School and the Department of African and African- American Studies at Harvard University.

If you would like to join Professors George and West as a public signatory to this statement, please submit your name and title and affiliation (for identification purposes only) via email to jmadison@Princeton.edu(link

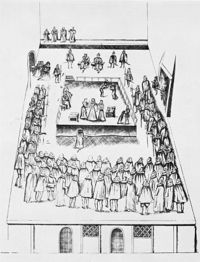

The executioner held up the severed head of the Queen of Scots for all to see — but horror as the hair separated from the head, and the head dropped to the floor. There was a stunned silence from the spectators — the Queen, once considered the most beautiful woman of her time, had lost her hair and vanity dictated the wearing of a wig.

The executioner held up the severed head of the Queen of Scots for all to see — but horror as the hair separated from the head, and the head dropped to the floor. There was a stunned silence from the spectators — the Queen, once considered the most beautiful woman of her time, had lost her hair and vanity dictated the wearing of a wig. In the ensuing conflict, the Scots were

In the ensuing conflict, the Scots were

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo After reaching agreement on all these issues, Trist drew up an English-language draft of the treaty and Cuevas translated it into Spanish, preserving the idiom and thought rather than the literal meaning. Finally, on 2 February 1 1848, the Mexican representatives met Trist in the Villa of Guadalupe Hidalgo, across from the shrine of the patron saint of Mexico. They signed the treaty and then celebrated a mass together at the basilica.

After reaching agreement on all these issues, Trist drew up an English-language draft of the treaty and Cuevas translated it into Spanish, preserving the idiom and thought rather than the literal meaning. Finally, on 2 February 1 1848, the Mexican representatives met Trist in the Villa of Guadalupe Hidalgo, across from the shrine of the patron saint of Mexico. They signed the treaty and then celebrated a mass together at the basilica.